Just a Soldier’s Wife?

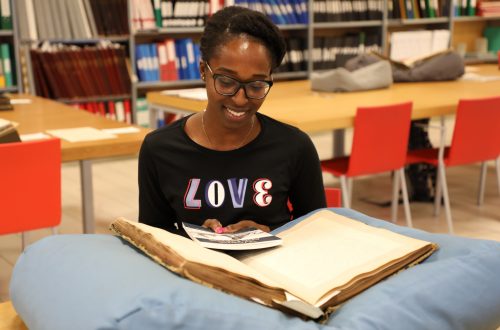

Margery Corbett Ashby was the first female candidate to stand in a Parliamentary Election in Birmingham. Rachel Gillies reflects on her achievements and how both the press and voters responded to her campaign.

Cast you mind back to December 2019. Just seven months ago we were heading to the polls. More than any election before, the misogyny directed towards female candidates was laid bare, with some prominent candidates even questioning whether they had a future in politics in the face of online vitriol, threats and even attacks on premises.

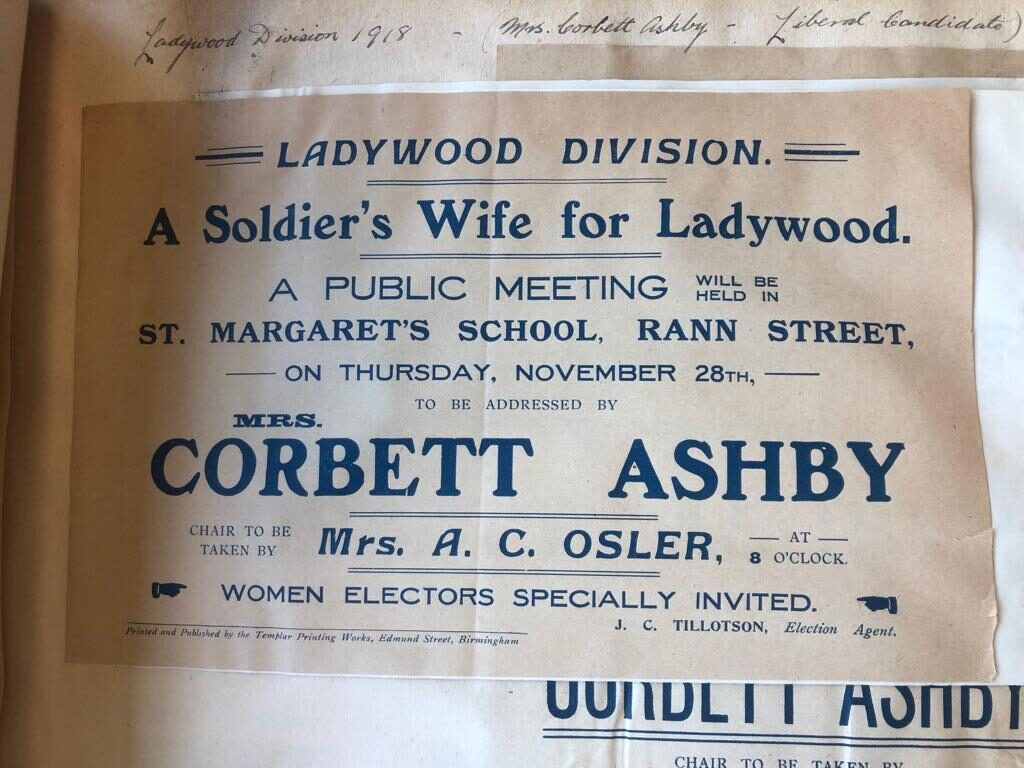

Imagine then, the situation for Birmingham’s first female candidate at a Parliamentary Election, way back in 1918. The ‘Khaki Election’ was so called because it took place just weeks after Armistice Day. Margery Corbett Ashby, as a Liberal candidate for Ladywood, would undoubtedly have been subject to a level of scrutiny, and possibly abuse, that we can still see echoes of today.

When the first women were granted the vote in February 1918, it was after decades of campaigning in the face of huge hostility – from both the political establishment and the press. Often portrayed as hysterical or immoral, campaigners were at pains produce propaganda to counteract these negative portrayals.

It’s maybe no surprise then, that when voters in Ladywood Division were first asked to elect a woman, election literature presents them with an image of a demure mother, holding her smiling son under the declaration that voters should vote Mrs. Corbett Ashby as ‘A Soldier’s Wife for Ladywood’. ‘As a wife and mother’ she promises to carry out voters’ wishes. Apparently the idea of a woman being championed for her own merits wasn’t seen as a vote winner.

Image courtesy of Birmingham Archives and Collections

Yet Margery Corbett Ashby was far from a passive wife and homemaker. As far back as 1901 she had formed the ‘Young Suffragists’ with her sister and friends where she lived in East Sussex. It was the start of a long career as an active and prominent campaigner for women’s suffrage and political representation, which even led to her becoming President of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance in 1923 until 1946.

By the time she stood as one of only 17 female candidates in 1918, she had already gained a Cambridge Education (Degrees were not awarded to women at the time) and had travelled around Europe to further the cause of female suffrage.

Image courtesy of Birmingham Archives and Collections

There is also evidence within newspaper articles that Margery Corbett Ashby was an articulate, passionate public speaker. In the run up to the ballot, all candidates held regular public meetings, where voters were able to question the candidates. When asked ‘Who is responsible for the housing conditions round here?’ at one such event, The Birmingham Mail reports her response:

Ultimately yourselves, the voter. You have never taken sufficient care in choosing your representatives to Parliament. Housing is the biggest of the social problems, and now that you women have been given the vote for the first time I look to you to support a candidate who is in earnest about this problem. We women care about housing very much, and I care about it very much. I want to see decent houses for everyone, and if returned I shall do my utmost to secure them.

Ladywood Liberal Candidate Margery Corbett Ashby when asked who is responsible for housing conditions.

Her candidacy was ultimately unsuccessful – she gained just 11.5% of the vote, with 1,552 votes. The seat was won by a large 6,833 margin by Unionist Candidate Neville Chamberlain, whose family name and time serving in government as part of the war effort made him a firm favourite from the outset. The Labour candidate, Union organiser and John Kneeshaw gained 19% of the vote with 2,572.

Despite these losses, there is a real question as to whether it was a genuine defeat. Now, as then, not all political candidates stand in elections with the expectation of winning, but instead use the platform to advocate for specific political issues.

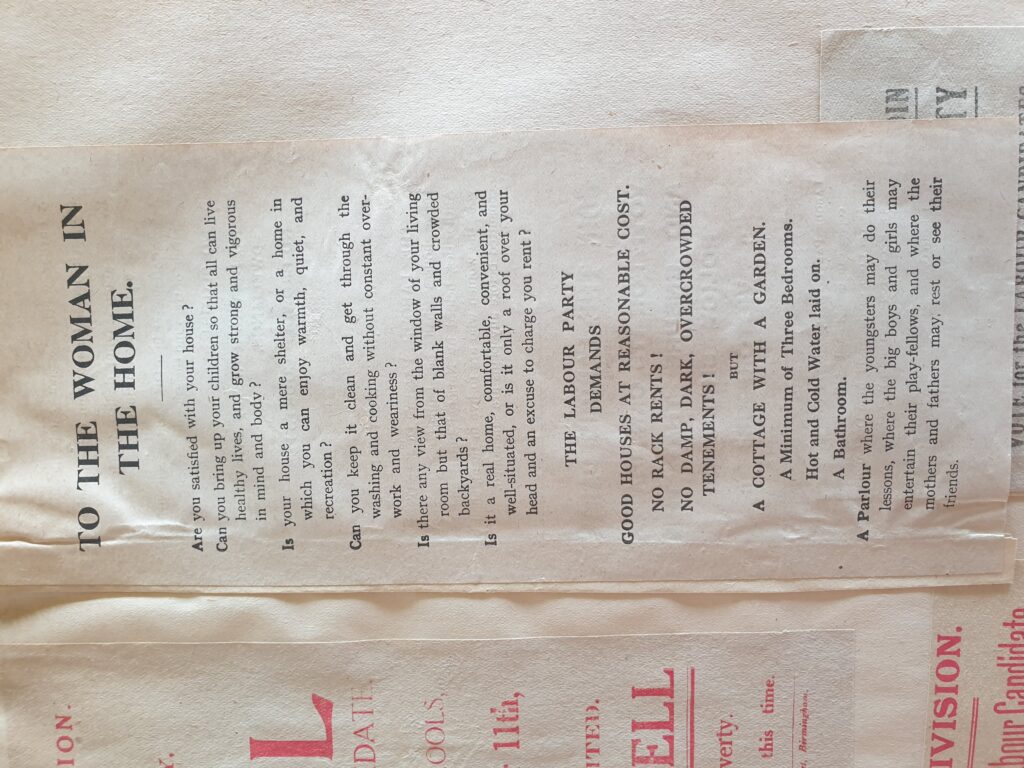

Looking through the propaganda elsewhere in Birmingham for the election, there are real efforts to appeal to newly enfranchised women. The Labour Party in Handsworth District even addressed a whole leaflet to women about housing policy in the belief that women would be attracted to promises of better housing conditions. Could it be that Margery Corbett Ashby helped to raise women’s issues in a way which would not have happened otherwise?

Image courtesy of Birmingham Archives and Collections

So what became of Margery Corbett Ashby? In a particularly scathing Editorial, the Birmingham Mail declared her:

…almost a stranger to Birmingham, and after she has flitted fitfully across the stage of this electoral contest, will no doubt vanish back into the unknown.

Birmingham Mail Editorial, 5th December, 1918

It was correct in stating that she would not make any impact on Birmingham’s politics, but this contest was the first of eight total election campaigns she fought, either as a Liberal Candidate or an Independent Liberal. She lived to the age of 99, attended the Versailles Peace Conference and the Geneva Disarmament Conference and was made a Dame in 1967.

Furthermore, she is possibly the only woman to have played an active part in both the pre-WW1 campaign for women’s suffrage, and the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s. Her last political demonstration was at the age of ninety-eight when she took part in the Women’s Day of Action in London.

Her name is engraved on the statue of Dame Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square.

Image taken by Rachel Gillies – April 2019

There is a remarkable interview with her in the BBC Archives from 1972, where she is interviewed by Joan Bakewell. Dame Corbett Ashby discusses her political life, including her experience of sharing a political platform with the Pankhursts.